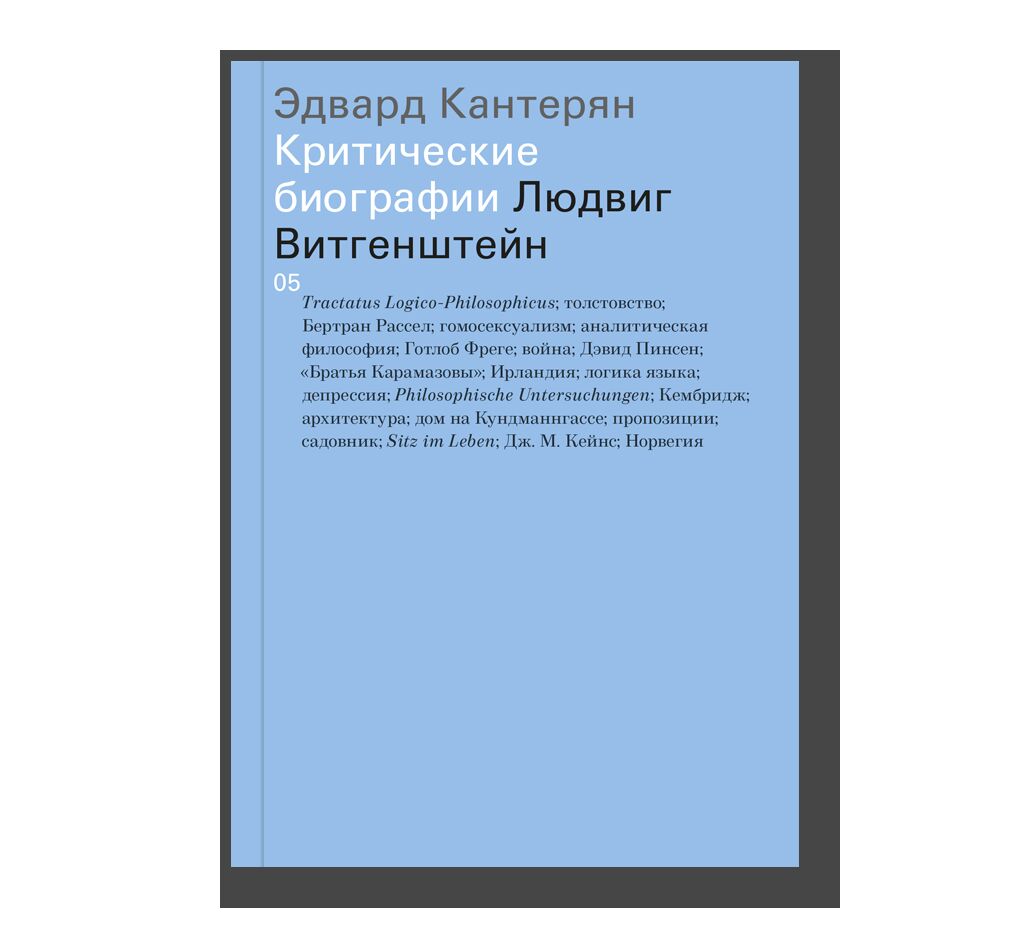

Ludwig Wittgenstein

- Year: 2016

- Language: Russian

- Publisher: Ad Marginem

- ISBN: 9785911032951

- Page: 248

- Cover: paperback

- About the Book

A new biography of Ludwig Wittgenstein—brilliant intellectual, great philosopher and humanist, who often felt himself a “weak, pathetic, and oppressed man seeing his own life as a problem.”

The author of the study considers biographies of charismatic personalities of the modern era a no less interesting topic than the analysis of their outstanding works (of art, philosophy, or science). Edward Kanterian’s book is an attempt to distract us from the generally accepted idea of admiration of Wittgenstein’s genius by introducing episodes from the philosopher’s personal life, which include two world wars, lasting bouts of depression, the refusal of a huge inheritance for the sake of charity, and work as a rural teacher for many years.

In 1920s Wittgenstein’s personality was already surrounded by an aura of mystery, and within the academic milieu—of indiscreet admiration. His friend and translator, the young philosopher Frank Ramsey wrote: “We live in a truly great time for thinkers: Einstein, Freud, and Wittgenstein—all of them are alive and at the same time they all live in either Germany or Austria…” However, apart from the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Wittgenstein saw only one book of his published in his lifetime—a self-made orthographic dictionary for children, which is now a bibliographical relic. And even his cult work Tractatus was published with difficulty, three years after it was finished, thanks to Bertrand Russell’s protection.

In comparison with other Wittgenstein’s biographers, Kanterian does not strive to put together these and many other obvious contradictions to present a whole image of his hero, paying as much attention to his philosophy as to his various, and sometimes extravagant, hobbies: “naive and stupid” Hollywood films, Rabindranath Tagore's poetry, the Tolstoyan movement, religion, medicine (Wittgenstein invented a gadget for blood pressure measurement), and architecture (at the end of 1920s, together with Paul Engelmann he designed a family home for his sister Margarete).

Further chapters in the book are devoted to the analysis of Wittgenstein’s philosophical works, and apart from Tractatus this includes Philosophical Investigations, published after his death in 1953. However, Kanterian, having made his goals clear beforehand, does not go into detail, indicating only the general direction of Wittgenstein’s thinking. At first, it was an atomic perception of the world as a system of linguistic propositions: “…we try to put our concepts in order to be able to clearly distinguish what can be said about the world. We are confused about what we can say. The act of making all this clear is called philosophy.” Wittgenstein’s belief in one philosophical concept evaporated over time, he started seeing analytical philosophy as only one of the methods for describing the world, and language as a dynamic organism and not as a static structure. Thus in the late period, Wittgenstein drew an especially clear distinction between science and philosophy, considering the latter as something that “should be presented only as poetry.”

“Philosophy is again and again accused of not, in essence, moving forward, of us still being focused today on the same philosophical problems that interested ancient Greeks. <…> The reason for that is that our language remains the same and thus again and again inspires us to ask the same questions.”