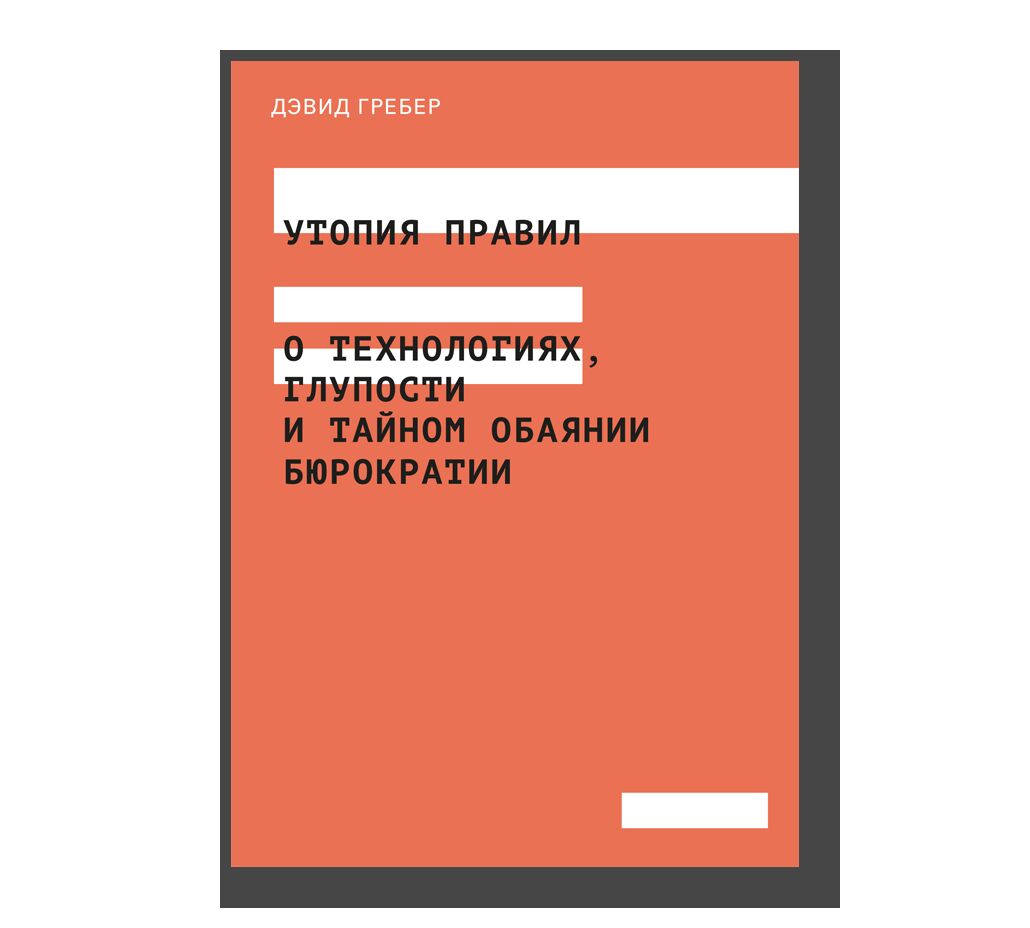

The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy

- Year: 2016

- Language: Russian

- Publisher: Ad Marginem

- ISBN: 9785911033156

- Page: 224

- Cover: hardcover

- About the Book

A collection of essays by anthropologist and activist David Graeber looks into the phenomenon of total bureaucratization of life and the reasons this problem is increasingly neglected. If in the 1950s and 1960s bureaucracy was the object of many studies, today, when ‘it informs every aspect of our existence’, people seem to have forgotten about it.

‘Someone once figured out that the average American will spend a cumulative six months of her life waiting for the light to change. I don’t know if similar figures are available for how long she is likely to spend filling out forms, but it must be at least as much.’ Drawing our attention to the problem of bureaucracy, anthropologist David Graeber offers several possible lines of critique of the increasing bureaucratization of life.

In the first essay, Graeber introduces what he calls ‘the iron law of liberalism’, according to which, any reform intended to reduce red tape will have the ultimate effect of increasing it. He explains this paradox by the fact that the bureaucratic system, which requires endless paperwork, has become our natural habitat and therefore might appear the only possible way of organizing a society. Questioning the rationality and efficiency of such organization, Graeber points out several of its fundamental flaws, which include ‘structural violence’ and lack of technological progress: ‘we’re not nearly where people in the fifties imagined we’d have been by now. We still don’t have computers you can have an interesting conversation with, or robots that can walk the dog or fold your laundry.’

The most dangerous effect of bureaucratization, however, is that following its rules turns into a kind of game, which replaces the authentic ludic element of life, which is improvisation. Instead of creativity, we compete in filling out forms. Warning the reader against such escapism, Graeber reminds us of the 1968 slogan ‘All power to the imagination!’ and the fact that our world is not ‘a natural fact, even though we tend to treat it as if it is—it exists because we all collectively produce it. We imagine things we’d like and then we bring them into being.’