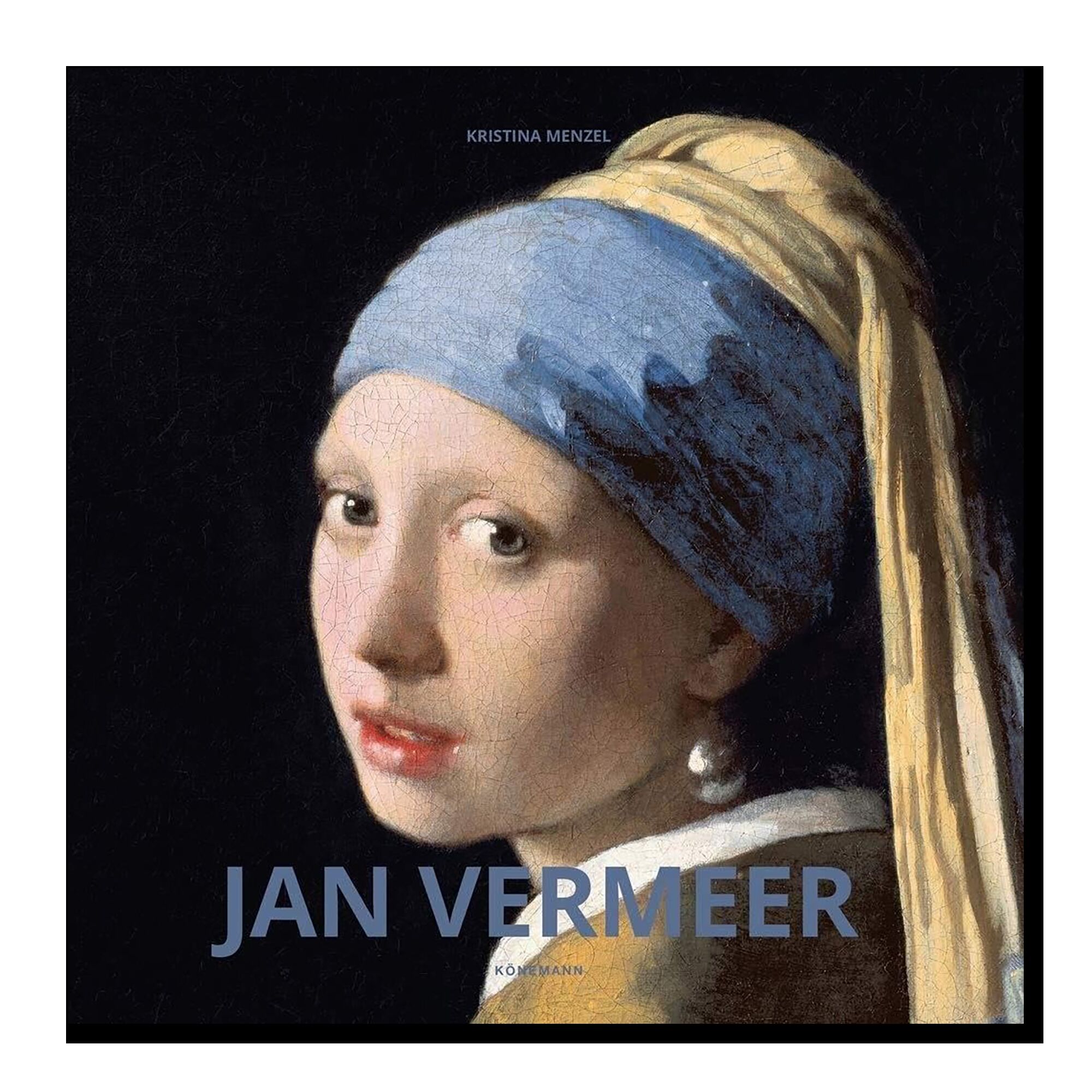

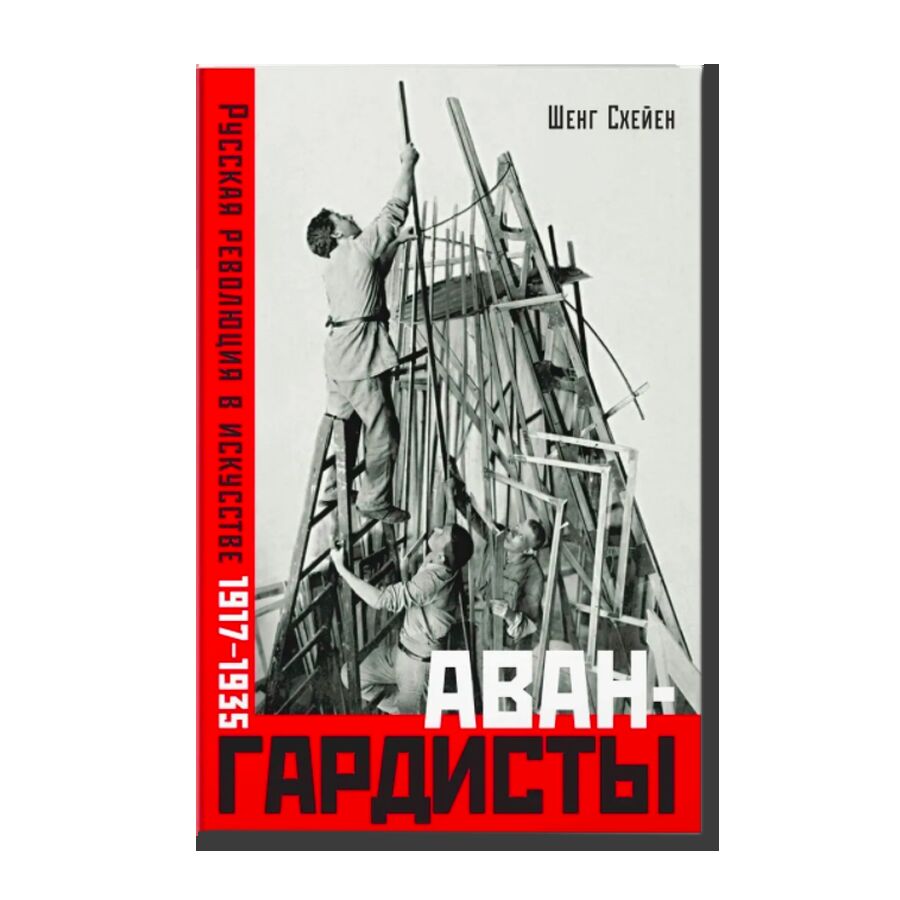

The Avant-Gardists. The Russian Revolution in Art, 1917–1935

- Year: 2020

- Language: Russian

- Publisher: КоЛибри

- ISBN: 9785389143562

- Page: 512

- Cover: hardcover

- About the Book

The Avant-Gardists. The Russian Revolution in Art, 1917-1935 by Sjeng Scheijen is a fascinating account of the rise and fall of a group of artists who revolutionised art, but who were eventually crushed by the Soviet state. Drawing on previously inaccessible archives Sjeng Scheijen has created a vivid portrayal of this extraordinary period in the history of modern art. I read it in Dutch, but an English translation is forthcoming.

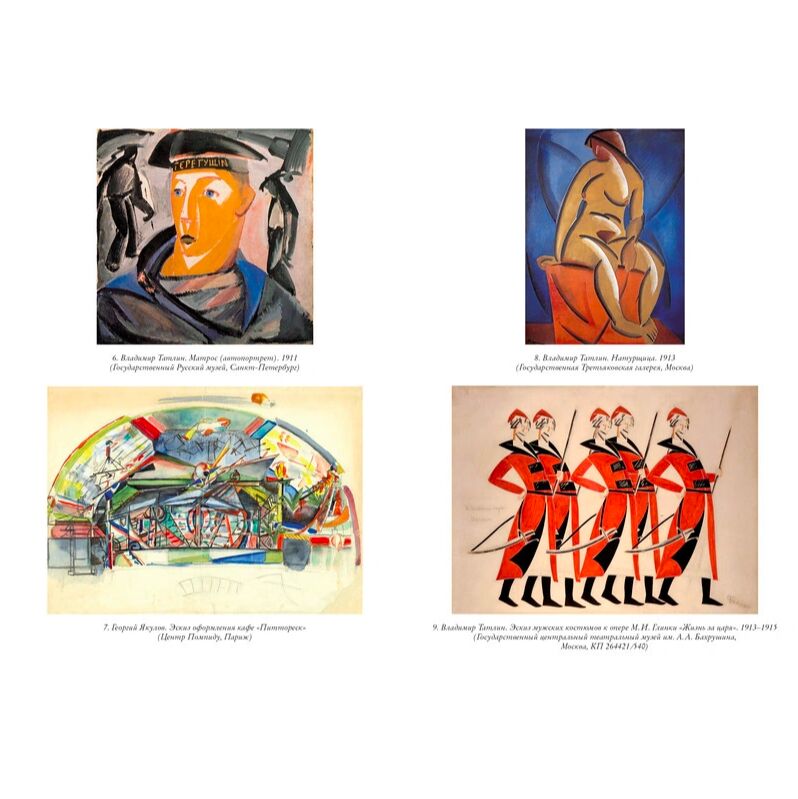

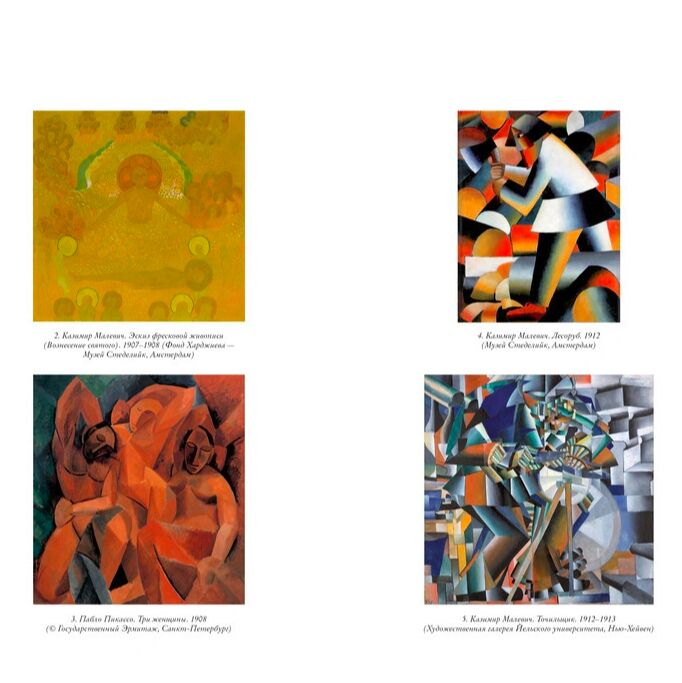

It may seem politically naive now, but many of the Russian avant-gardists embraced the Bolshevik revolution. They had been rejected by the old czarist system and many genuinely believed that their work aligned with the ambition of the Bolsheviks to establish a new society. For a brief moment some artists, including Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin, became officials within the newly established state institutions. They set out to reform art academies and other art institutions, but it didn't take long for opposition to take hold, in part because numerous traditionalists still held powerful positions, in part because the bolsheviks favoured art that would appeal to the masses and that could serve as propaganda. Less than a year after the Russian revolution the avant-gardists would once again be marginalized. Some, such as Chagall and Kandinsky, emigrated, others were prosecuted or murdered, yet others adapted to the whims of the new rulers so as to continue working.

Today the work of Malevich, Tatlin and El Lissitzky belongs to the canon of modern art. Their work is included in the collections of the world's major museums of modern art. What one doesn't see from merely looking at the artworks is the struggle that went into creating these works, the enthusiasm with which the Russian avant-gardists explored new forms and the tenacity with which they fought for their ideas, despite growing opposition. It is this that Sjeng Scheijen masterfully depicts in The Avant-Gardists.

As Sjeng Scheijen points out, El Lissitzky was one of the first abstract artists, if not the first, who didn't develop abstract painting himself, like Mondriaan, Kandinsky and Malevich, but who adopted it as a student. This may not sound like a great merit, but it shows something else. Abstract art was not an end point, the culmination of a path to ever greater abstraction or simplification, it marked a new beginning and offered opportunities for developing a novel and personal style, as can be seen in the work of abstract artists of later generations, such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Agnes Martin, Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella, Lucio Fontana and Gerhard Richter to name but a few.

I have long been an admirer of the work of Malevich and El Lissitzky. Many years ago I saw a large retrospective of the Russian avant-garde at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt. When the exhibition travelled to Amsterdam I went to see it a second time. I have since visited various other exhibitions of the Russian avant-garde. I love the spatial composition in the work of Malevich and El Lissitzky. But above all else to me the work the Russian avant-gardists attests to the freedom and power of the imagination.